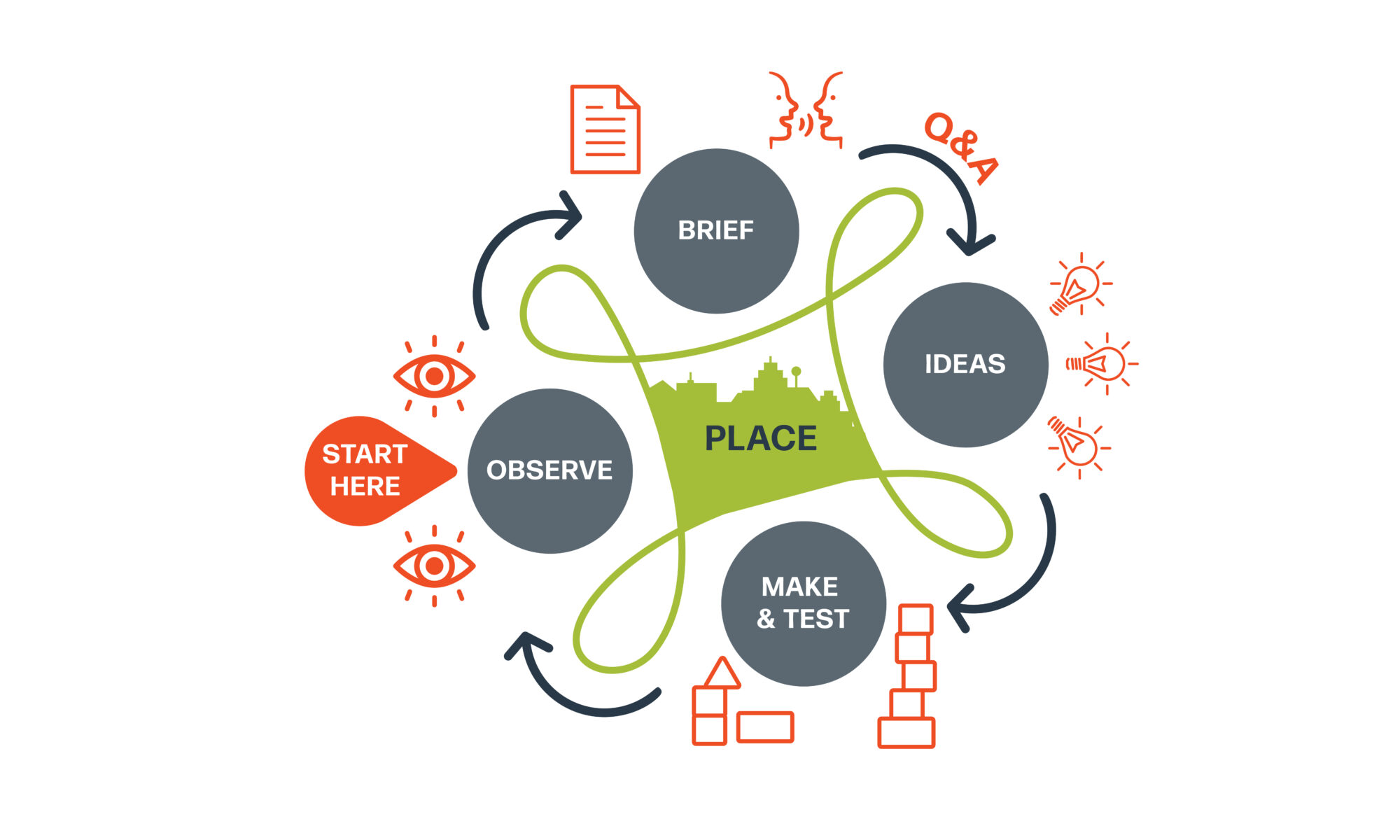

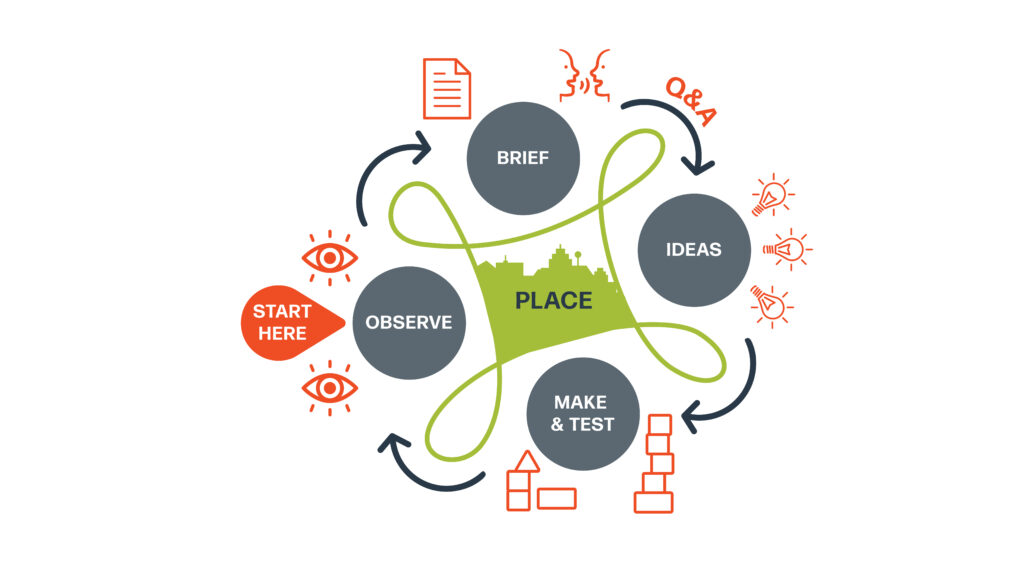

Continuous place-based design is distinct from its opposite: short-term design from anywhere. It connects designers more deeply to the places they are designing. The approach tunes users into the complex dynamics of place — the emergent needs and possibilities — and helps us find designs that are a better fit. It’s a dynamic approach that challenges the idea of designing fixed plans.

This motif arises from two foundational ideas in the Pattern Book: that we are working with complex systems, and that regenerative design involves changing mindsets.

Use this graphic — Downloadable, usable, shareable under CC BY-SA 4.0

Introduction the model

Engineers and architects often design buildings, but their true impact is on places — the communities and ecosystems that inhabit them. If we want our work to create genuinely positive outcomes for both humans and the wider living world, we need to move beyond an isolated focus on buildings and shift towards a deeper understanding of place.

Understanding place as a complex system

Places are complex systems, full of humans and other species, shaped by relationships and constant change. In such systems, we cannot fully predict the impact of the changes we introduce. Instead, we learn by doing — by making small interventions, observing their effects, and adjusting accordingly. Long-term engagement with place is essential for truly understanding how it works.

This gives us our first clue: design must be an ongoing process, not a one-off intervention.

The second clue is that every place is unique, and that uniqueness becomes even more pronounced the deeper we look. How can we possibly create designs that embrace such diversity? The living world offers a model that doesn’t rely on rigid masterplans—it works iteratively, testing variations, adapting over time, and responding to changing conditions. The result is a best-fit design for the specific ecological, cultural, and environmental context.

From the Pattern Book for Regenerative Design.

The shift to Continuous Place-based Design

If we take these two starting points seriously, then instead of asking “What do we want to do to this place?”, we should begin by asking:

- What is already here?

- What is needed?

- What is missing?

- What is beginning to change?

From this foundation, design can emerge gradually—guided by the dynamics of the place itself. Small interventions can be tested, refined, and expanded, always with an eye on how the system is responding. This shifts design from being a one-time act imposed from outside to an ongoing process that works with that place, learns from that place, and evolves alongside it. In The Regenerative Structural Engineer, we called this approach continuous place-based design.

The Key Stages in Continuous Place-Based Design

1. Observation

Rather than starting with a problem to solve, continuous place-based design starts with an extended period of observation. In this case, observation means more than a desk study or mapping exercise. It requires time spent in a place—experiencing it from different perspectives, noticing rhythms, interactions, and patterns of change. But observation isn’t just the first step — it’s a practice we return to again and again, each time we make a change.

2. Brief

From observation, we begin to sense what is needed. The brief emerges as a way of distilling these needs into a set of design requirements.

Unlike traditional design, which aims to fix the brief upfront, continuous place-based design sees the brief as a continuously evolving set of requirements. Each intervention in a system changes the system — and with it, the requirements. Continuous place-based design embraces this reality. The brief evolves over time, but it doesn’t necessarily converge to a single, finalised solution. Each iteration is the best response for now, while recognising that every intervention changes the system — and with it, the design brief itself.

3. Ideas

The creative phase of the process is deeply influenced by the place itself. The designer’s role is not just to generate ideas, but to facilitate the emergence of ideas from place — to see what is latent, what is already forming, what might be supported. At the same time, by embedding ourselves in a place, we too become part of its system. Our ideas are shaped by this connection, rather than being external impositions.

4. Make and test

This is where we intervene — where design moves from thought to action. We begin making changes to the system.

Interventions can range from running experiments to test ideas, to large-scale changes — though an important principle stands: start small, learn, then scale out. Through acting, we begin to see how the system responds.

For example, in a housing development, instead of building an entire estate at once, we might start with a few houses, observing how the place changes and adapts before expanding further. The goal is not to eliminate uncertainty, but to work with the unforeseen consequences of our design decisions — using them as feedback to refine and update the brief.

Back to Observation Again

Having made our changes to the system, we go back to observation — but we are not back where we started. The system has changed, and so have we. We become more embedded in the system we are designing with, better able to facilitate change that will bring forward thriving in that place.

Conclusions

We cannot learn if we simply hop from one project to another, designing in isolation. The longer we stay with a place, the deeper our understanding grows—and the better we become as designers. Over time, this commitment to learning allows us to create thriving places that are much more in sync with their human and ecological context.

Role in the Pattern Book

In practice, Continuous Place-Based Design is a process that requires a whole set of tools at each stage. These are set out in Pattern 06 in the Pattern Book for Regenerative Design.

Using Continuous Place-Based Design in different contexts

- Personal regenerative practice — use this model to think about how you integrate your local context into your personal design practice.

- With developers and asset managers — use Continuous Place-Based Design to explore how you can meet your client’s goal while building thriving into the community and ecosystem.

Related motifs

Better Feedback, Changing Mindsets, Complex Systems, Short-Term Design from Anywhere, Thriving, Working with Living Cycles.

Recommended courses

-

Seeing the System — a systems led intro to regenerative design

Price range: £175.00 through £375.00 -

Regenerative Design Lab — Cohort 6

Price range: £950.00 through £2,800.00

-

Signs of local weather

I’m enjoying being absorbed by The Secret World of Weather, by Tristan Gooley. It reveals to the reader secret signs all around us about how the weather is likely to behave. Signs that hide in plain sight, that we have forgotten to notice. The repeating theme in the early chapters: modern forecasting models deal with…

-

On pattern spotting

Pattern is a word I use a lot. Recently, a reader wrote to say how much they appreciated this use of pattern language in my writing. And that made me pause today and think about why patterns matter so much to me. A book I regularly return to, usually towards the start of the summer…

-

Incline? Uncline? Recline?

I caught myself wondering in a workshop this week, what is the opposite to decline? Incline? Uncline? Recline? A bit of context. I often look at places in need of repair and think why has nobody fixed that yet? Perhaps, in the past, my automatic response would have been to say because there isn’t a…

-

340-degree vision

I read on a fact sheet that guinea pigs have 340-degree vision. On a horizontal plane they can see almost all around. Imagine! Their only blind spots are directly behind and a small patch directly in front of them. That’s because they are prey animals. They spend their whole waking time observing their environment for…

-

Visions that abstract us/ visions that ground us

Many vision statements float in the abstract. To be a global leader… To minimise store-to-door time… They sound clear, but they ignore the ecology and community that make the work possible. At best, such visions are inert to these realities. At worst, they succeed only at the cost of them. A regenerative vision is rooted…

-

Get on the ground and start moving around

In the early days of the internet, you had to know a website’s URL in order to visit it. Companies like Yahoo! set themselves up as way-finders. Visit their site and you could find links to popular places on the web. All organised under headings like a giant directory. And then a little company called…

-

Teaching theory versus the inconveniences of reality

Theory is abstraction. It is an understanding that is distilled of the inconveniences of reality to allow us to make predictions about that reality. Most engineering degrees start with the theory. Vast columns of theories stacked one on top of each other in piles called things like Mechanics 1 Mechanics 2 Mechanics 3 And then…

-

Pattern book field notes – action learning and continuous place-based design

This week I took my copy of the Pattern Book to Cambridge. (Its second visit: in July I dropped it — and my laptop — in a puddle. Both recovered, and this time was less eventful.) I was there to deliver my annual September workshop for the new cohort of students on the Sustainability Leadership…

-

Learning as a design process

In a flip of yesterday’s post — if design can be a learning process, then learning can be a design process too. What would it look like to approach learning the way we approach design? Design begins with intention. It asks: how do I take an existing situation and make it better? That invites us…

-

Design as a learning process

Many projects treat design as a problem with a fixed answer. But what if we treated design as learning journey? In a complex world, design needs to be a responsive process. This means observing, setting intentions, developing ideas, testing them and seeing what happens. With each iteration of this process we get a better understanding…