Processes make life easier, help us involve more people, guarantee quality and conserve our attention for other things. But only if they work.

The first time we do something, part of the work is figuring out how to do it all. If we are likely to that thing several times, figuring out a process means we don’t have to make those decisions every time.

Creating a process also helps other people over the activation energy hurdle and, where questions of quality or compliance come in, give us a way of making sure it is done properly And this work invested in creating a process frees up cognitive load to think about other things.

In a sense, we relinquish our autonomy to processes for the benefits they yield. But when the process no-longer provides those benefits, it starts to cause problems.

If for instance the circumstances in which the process was created has changed, but the process stays the same, then it becomes an ill-fitting glove on the hand of someone trying to take action. It constrains us, it is uncomfortable and we are constantly aware of it.

Things become worse when you don’t have a choice — when your organisation has told you you have to use this process. Then you no-longer feel the benefit of the loss of autonomy — it becomes a burden. And this can quickly lead to cynicism.

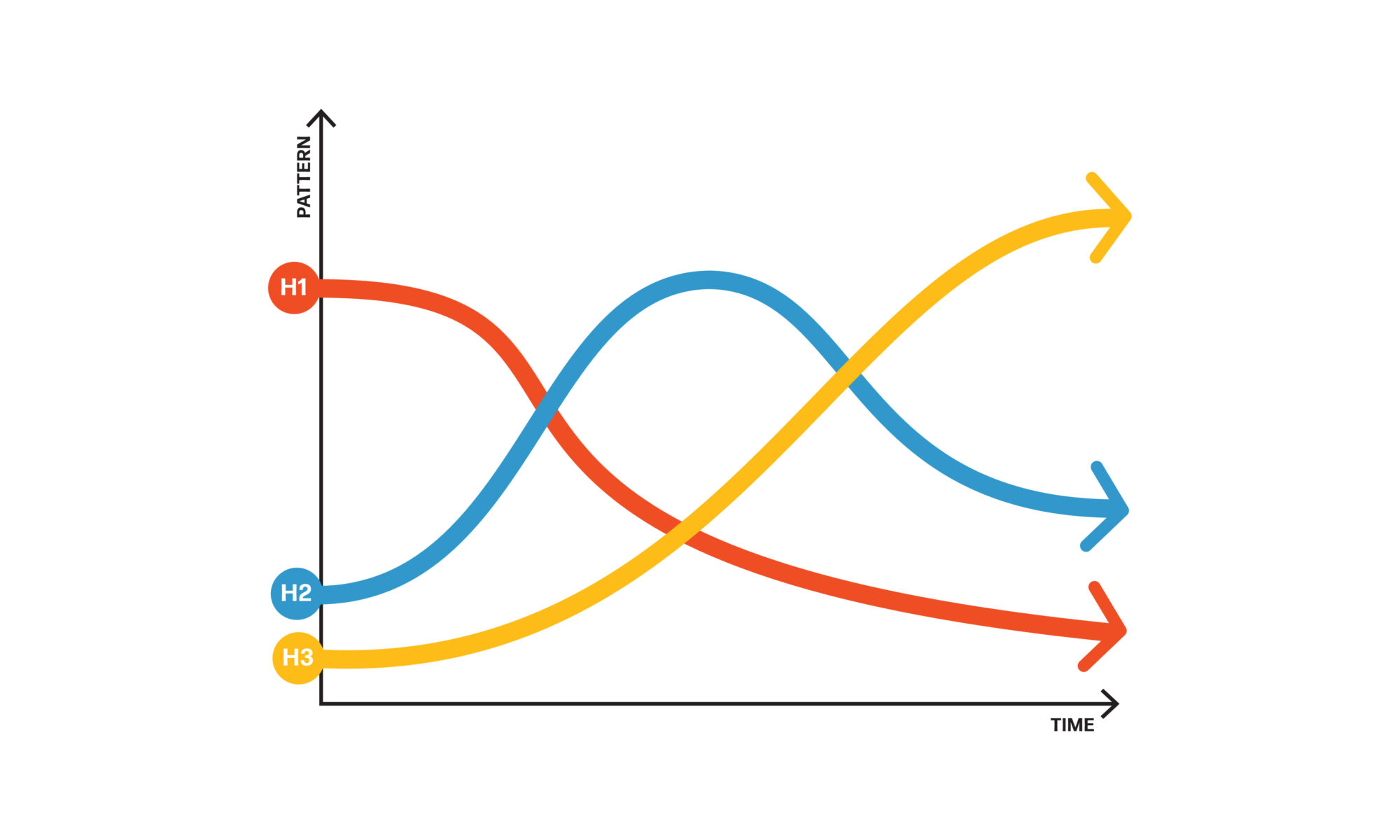

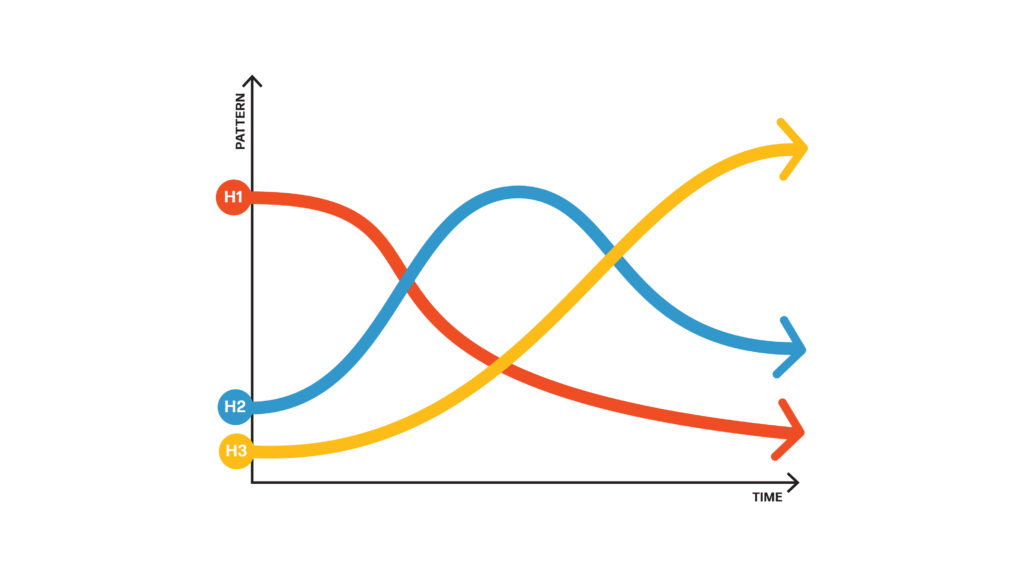

So what can you do? I see three levers: improve, remove or emphasise.

Improve — if that process is there to do work for you, but is no-longer doing its job, then make it work. This requires new up-front energy to reap down-stream reward. You may not want have to do this work, but the conditions have changed and you’ll continue to pay the price until you update procedures. A badly fitting process creates friction every day, which is energy sapping. If you are in a position of authority, then you hold responsibility for the processes your staff are obliged to work with.

Remove — it’s much more common to add processes than take them away. Lean thinking in process design is all about stripping everything and then building back up with the essentials that do just enough to create a good product, whatever that might be.

Emphasise — and if you are stuck with the process, as many in larger organisations will be, then emphasise the value that the process is creating. If it generates data, make that data visible and valuable to the people using the process. If it helps keep people safe, then emphasise that message less it gets lost and then ignored.

Improve, remove, emphasise. You could think of this as a process for processing processes.