Helping people think regeneratively, work creatively and make change happen—one project at a time.

The Regenerative Design Lab

A six-month transformational programme for leaders and future leaders to develop and apply regenerative thinking

Apply by 12th January to be considered for Cohort 6.

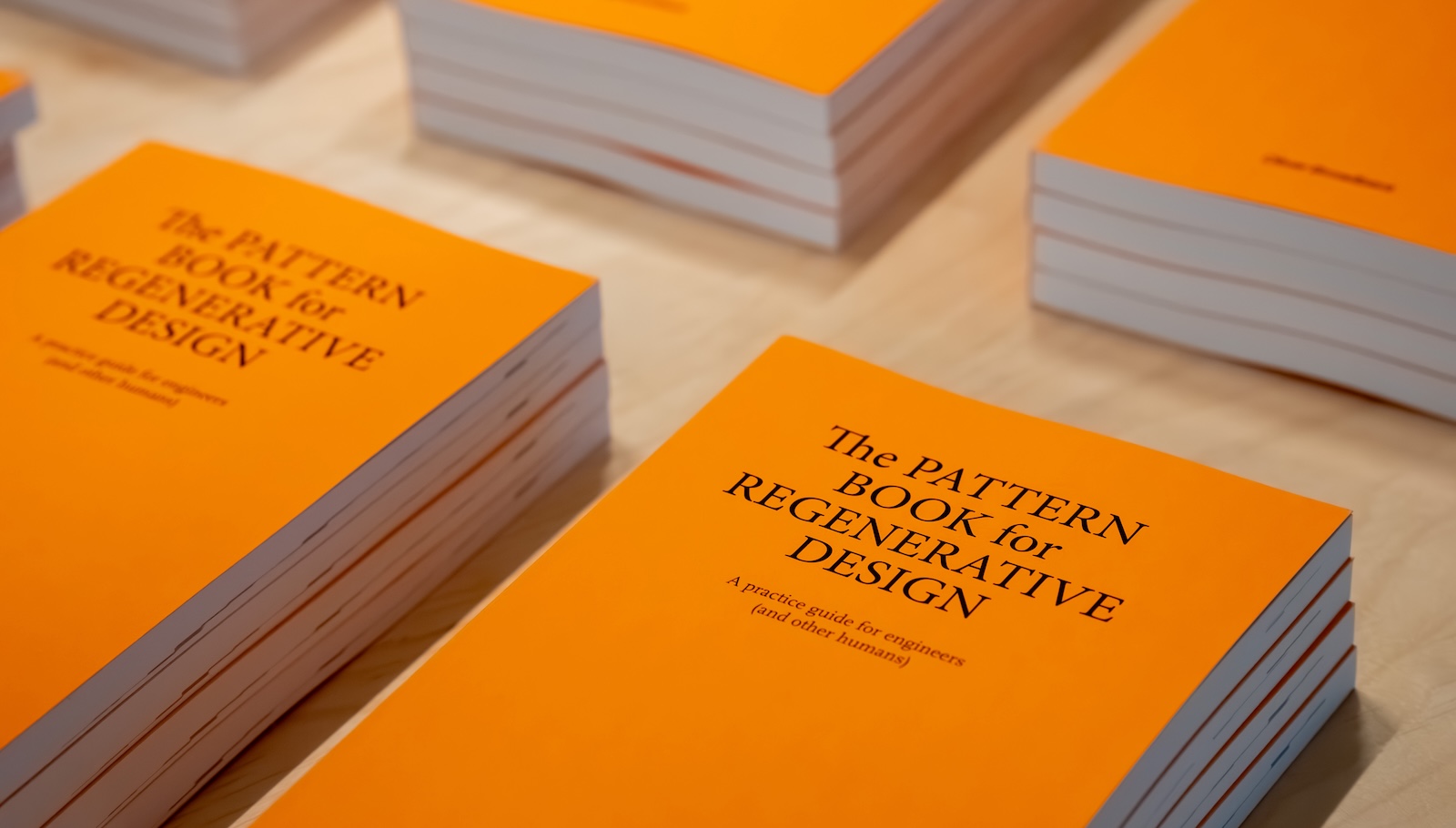

The Pattern Book for Regenerative Design

A practice guide for engineers (and other humans)

Seeing the System

Our online introduction to Regenerative Design – runs Feb 26 to Mar 19 2026.

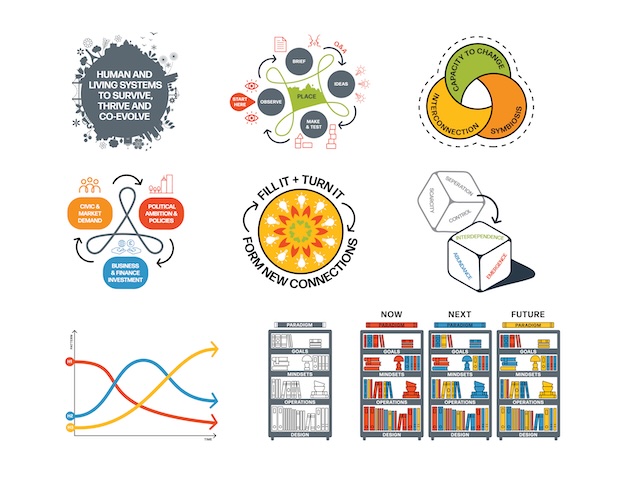

Tools for Regenerative Design

Our top tools for regenerative design, free to use and available for download.

Most popular open courses

Most popular in-house courses

The blog: For Engineers (and other humans)

Oliver’s daily(ish) blog on creativity, regenerative design and practical philosophy drawn from across my teaching, writing and collaborations. Sign up for Oliver’s weekly digest by clicking here and choosing the appropriate button.

Latest posts

- When a group of learners becomes a living systemAll week we’ve been interviewing candidates for Cohort 6 of the Regenerative Design Lab. With such a strong range of applicants, it’s been a real privilege to spend …

Continue reading “When a group of learners becomes a living system”

- Hope, fullyPart of the role of the regenerative designer is to develop and nourish a view of a more hopeful future. This isn’t passive work — it’s active. Repeatedly …

- Unhelpfully agreeing to crap processesIn the Get It Right Initiative leadership workshops we spend time talking about behaviour, and time talking about process. Today I made an interesting discovery when I accidentally …

- How do you write a contract based on regenerative values?Today I’ve been thinking about that question as we finalise the participant agreement for the Regenerative Design Lab. People are about to hand over their money, and that …

Continue reading “How do you write a contract based on regenerative values?”

- On transforming time and system immunityMalcolm Gladwell claimed in his book Outliers that it takes 10,000 hours to become an expert in something. How many days is that? How many years? It’s not …

- 200 new Pattern Books please

So this happened over Christmas – we sold out of the Pattern Book for Regenerative Design. In fact we sold the last one on Christmas Day. That means …

So this happened over Christmas – we sold out of the Pattern Book for Regenerative Design. In fact we sold the last one on Christmas Day. That means … - Fellowship completeJust sharing some news of a big milestone in this work: the Commissioners have signed off the final report for my Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 …

News and highlights

Field notes from our training courses and news about what we are up to at Constructivist.

Latest articles

- 200 new Pattern Books please

So this happened over Christmas – we sold out of the Pattern Book for Regenerative Design. In fact we sold …

So this happened over Christmas – we sold out of the Pattern Book for Regenerative Design. In fact we sold … - Fellowship completeJust sharing some news of a big milestone in this work: the Commissioners have signed off the final report for …

- Big news — Cohort 6 Applications for the Regenerative Design Lab are now open

Our big news this week is that the application process is now open for Cohort 6 of the Regenerative Design …

Our big news this week is that the application process is now open for Cohort 6 of the Regenerative Design …Continue reading “Big news — Cohort 6 Applications for the Regenerative Design Lab are now open”

- Field notes: trying on the Systems Change Lab for size

Last week I had the privilege of facilitating an afternoon session for the Engineers Without Borders UK Systems Change Lab …

Last week I had the privilege of facilitating an afternoon session for the Engineers Without Borders UK Systems Change Lab …Continue reading “Field notes: trying on the Systems Change Lab for size”

- Starting to see the systemYesterday we kicked off our new introduction to regenerative design, ‘Seeing the System’. The premise is simple: seeing more clearly …

- Pattern book field notes – action learning and continuous place-based design

This week I took my copy of the Pattern Book to Cambridge. (Its second visit: in July I dropped it …

This week I took my copy of the Pattern Book to Cambridge. (Its second visit: in July I dropped it …Continue reading “Pattern book field notes – action learning and continuous place-based design”