Regular readers of this blog will know all about the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the universe will tend toward disorder over time.

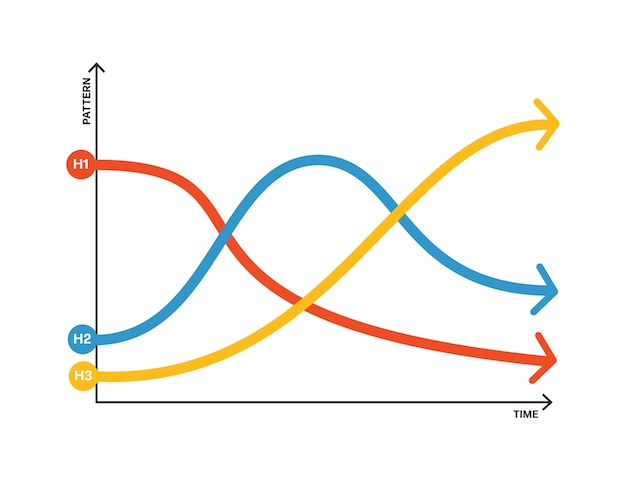

Thus any organised system will drift towards disorder unless energy is provided to maintain it. In other words, any project process or workflow that we set up will naturally start to fall apart unless the value it creates is worth the energy it takes to maintain it.

That means, folks, that when we set up a project process or a system it had better deliver some benefit.

My post yesterday was about effective communication systems. With the right design, we can create communication protocols that add value to how we communicate, making everyone’s work easier, perhaps even joyful!

But this process design is an art.

Make a process too complicated and no one will use it, and the thing falls apart. Mandate people to use it anyway and you will deplete their energy for other valuable thinking.

And processes need love. Fail to show them care and attention, bits will stop working, or no longer be relevant, or worse, people will default to easier-in-the-short-run processes that will cause headaches in the long run.

The pull towards disorder is never far away. The processes we design must supply enough benefit to hold things together.