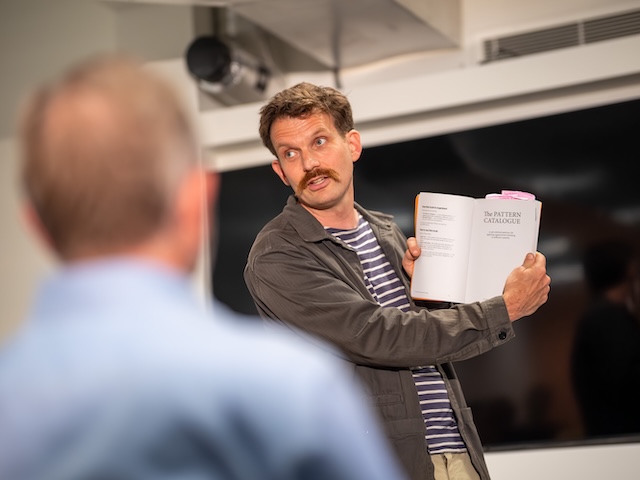

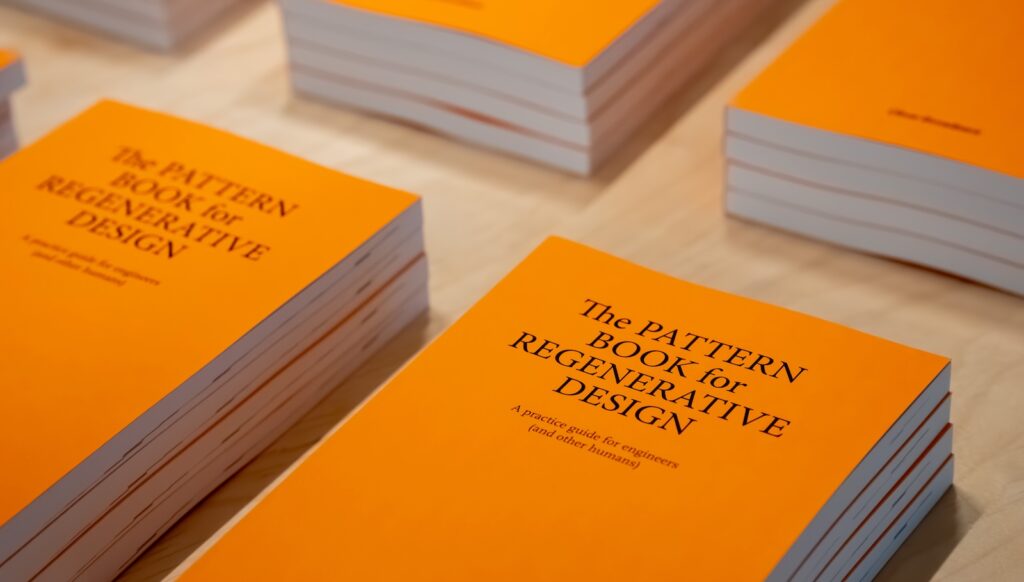

I was in Paris last week to deliver a creative thinking workshop for engineers. I did the presentation in English and the Q&A in French — a happy balance that let me be precise in theory and looser in conversation.

But I got a bit stuck translating ‘the Designer’s Paradox’ in French.

The Designer’s Paradox says ‘you don’t know what you want until you know what you can have’ (McCann 2001)

Asking for help here’s some suggestions I got during the day.

On ne sais pas ce que l’on veut avoir, tant que l’on ne sais pas ce que l’on peut avoir.

Translated back into English, this reads as ‘one doesn’t know what one wants for as long as one doesn’t know what one can have‘. It’s a fair translation, but long and literal.

Then came:

‘Savoir ce que l’on veut, ou vouloir ce que l’on peut.’

Literally — know what you want or want what you can. It’s crisper and I like the rhythm. But the meaning drifts — it’s more about choosing between reality and desire.

Mashing these together, I came up with:

Savoir ce que l’on veut, savoir ce que l’on peut, vouloir le meilleur des deux

Know what you want, know what you can, want the best of both. But that isn’t really French!

In searching for the French version of the Designer’s Paradox, I’ve found another.

Translate the meaning and lose the poetry

Translate the poetry and lose the meaning.

That’s the translator’s paradox.