We are happy to announce the release of our latest report, detailing the findings from the third cohort’s six-month exploration into how policy changes can unlock regenerative design. Our report is now available for download, the findings of which offer a starting point for our next cohort investigating the intersection of policy and regenerative design.

Continue reading “Report Release Announcement: Exploring Policy and Regenerative Design”How to Have Ideas: Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There

Last week, we were at the Institution of Structural Engineers delivering our ‘How to Have Ideas’ workshop to graduate engineers from Ridge Consulting.

Creative thinking is often the gap in the formal education and training of engineers. Yet, in the context of the climate emergency and a rapidly changing economy, creative thinking is crucial for developing designs that meet the needs of people and our wider ecology.

Continue reading “How to Have Ideas: Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There”Buying Bags of Kaleidoscopes: reflecting on how far ideas in teaching can travel

Today, Oliver concluded his series of six workshops as part of the Interdisciplinary Design for the Built Environment (IDBE) Masters program in Cambridge. In this final session, participants reviewed the material covered over the last five sessions, spread out over two years, and set objectives for their continued professional growth.

The series of six lectures aimed to integrate collaborative design skills into the Masters program, focusing on both creativity and collaboration.

Continue reading “Buying Bags of Kaleidoscopes: reflecting on how far ideas in teaching can travel”The Pattern Book – a new collaborative project in regenerative thinking

Earlier this month, we unveiled the Pattern Book project, an innovative workbook designed to guide professionals in the built environment towards regenerative design principles. The Pattern Book is the next evolution in the development of the Regenerative Design Lab.

New patterns for the future

The Pattern Book aims to be an emergent, collaborative resource, offering a collection of tools, techniques, and resources under Creative Commons.

Continue reading “The Pattern Book – a new collaborative project in regenerative thinking”“We see in patterns, we recognize patterns, we create patterns. To create a world in which construction brings about thriving rather than destruction, we need new patterns for thinking about how we design and build,”

Oliver Broadbent

Lunar Sprint: Aligning Work with Living Cycles

The regenerative designer uses living systems as a guide for how to live as part of and contribute to the wider thriving of our living systems. The Living Systems Blueprint is our rough guide to thinking and designing like living systems.

Understanding living work rhythms

One of the dimensions we need to consider is how we relate to rates of work. Very few living systems work at a constant rate; rather, they go through cycles of production and restoration. These cycles of work often mirror the larger physical cycles that we all experience: the passing of the day, the lunar month, and the turning of the seasons. By aligning periods of work with times when there is more energy available, living systems can be more energetically efficient.

Humans in the Global North once lived much more closely in tune with natural cycles. But the availability of cheap energy has decoupled many of our activities from these living rhythms. Yes, we still sleep every day, but the length of the working day does not necessarily reflect the amount of light available. Our system of weeks and months is decoupled from the living world, and there is very little variation in our patterns to reflect the seasons.

The Cost of Constant Output

The invention of the production line in the twentieth century created the ideal of producing constant output. But this requires a large amount of energy to maintain, and in the case of humans, that includes mental energy.

If we want to live and thrive within our ecosystem’s limits, it makes sense to think about how we too can return to more cyclical rhythms of working, ones that relate to the large-scale physical cycles that dominate the living world. This is where the concept of the lunar sprint comes into play.

Benefits of Cyclical Work Rhythms

Working in a more cyclical way offers several benefits:

- Human Thriving: Creating a balance between periods of work and nourishment that enable that work.

- Better Tuning: Helping us better tune in to what the living world is doing, allowing us to listen to its feedback and learn from how it works.

- Energy Alignment: Giving us the chance to align our work with times when there is more abundant energy available in the system.

- Inclusivity: Honouring and tuning into the rhythms of many people who menstruate, acknowledging their natural cycles.

Introducing the Lunar Sprint

Working with cycles is already familiar to people who use agile ‘sprints’—short bursts of activity to deliver a specific output followed by a period of rest, mirroring how living systems operate. The concept of the lunar sprint is to take the agile sprint one step further and map it to a physical cycle—the lunar month.

The lunar sprint operates between two poles: the new moon, when we think about what is possible, and the full moon, which is showtime, the day when we present our work. Here’s how the cycle of design work could map out:

- New Moon – The time of greatest darkness. Time to gather stakeholders and imagine what is possible, what the next phase of work could deliver.

- Waxing Crescent – Starting to turn ideas into plans. Lining up the resources to do this cycle’s work.

- First Quarter – Focus on producing output. Peak production. Turn off the critical voice and amass ideas. Fill the Kalideascope.

- Waxing Gibbous – Starting to edit and improve.

- Full Moon – The time of greatest light, when there are no shadows on the moon. This is the time to go live, present your ideas, launch the product, etc.

- Waning Gibbous – Harvest, write up, share the outputs, gather feedback. Pay and get paid.

- Third Quarter – Give back to the system that enabled you to do the work. Teach, mentor. Sharpen the tools and tidy up.

- Waning Crescent – Nourish yourself, read, reflect on what you have done. Rest in readiness for the next cycle.

- And repeat.

Living in Tune with the Living World through Lunar Sprints

The lunar sprint includes many of the usual parts of a project process, balancing these with paying attention to nurturing the parts of the system that enable us to do our work. By linking this work to a physical cycle, it allows us to step into living in tune with the living world. It enables us, in the words of Daniel Wahl, ‘to live the question’ of What if we were to live like the rest of the living world?

Models and frameworks for regenerative design – cohort 2 report now live

The news is that we have now published our report from the second cohort of the Regenerative Design Lab. Each cohort of the Lab represents an evolution in our shared understanding of regenerative design. The breakthrough in this cohort was to test tools, techniques and language that make regenerative design easier to understand. These methods bring much-needed clarity to the broader conversation about how work in the construction industry can create thriving.

Our reports are written to be shared; the content to be used. So download a copy and please do share with anyone who you think would be interested.

Cohort 4 Applications now open

Applications are now open to join Cohort 4 of the Regenerative Design Lab. For this cohort we are partnering with Chatham House Sustainability Accelerator to ask how can we create policy that delivers regenerative design. We are looking to build a mixed cohort of policy writers, designers and people interested in influencing policy. All the details on the cohort 4 page.

Announcing the Regenerative Design Lab Summer Research Workshop

The Regenerative Design Lab community is growing. In 2022, the first 20 people began their journey through our pilot of the lab. Now over 50 people have completed the lab programme (and some of them have been through twice!).

So now our work as conveners of the Lab is as much about nourishing this existing community of regenerative practitioners as it is about recruiting more. And so to help support and further the work of this group of change-makers, we are holding our second summer research workshop.

Continue reading “Announcing the Regenerative Design Lab Summer Research Workshop”5 questions on regenerative design

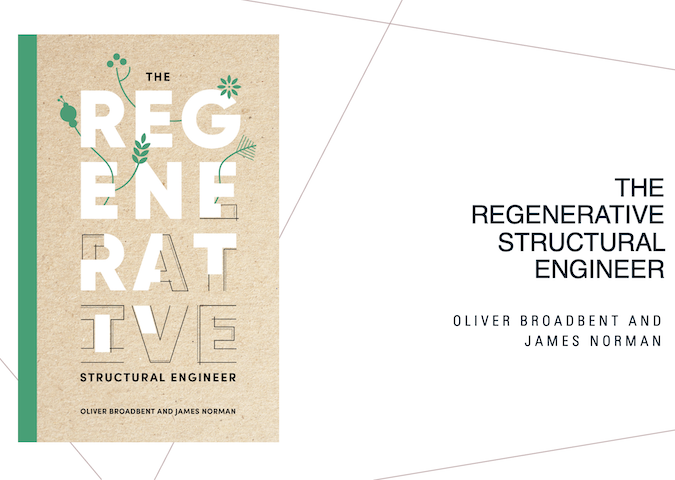

With five days to go until the launch of the Regenerative Structural Engineer, here are some questions that we would hope you can answer once you have read it.

- What is the difference between regenerative design and sustainability design? Is this just a new version of sustainability or is this substantially different. What does regenerative design mean anyway!?

- Why do we need to go beyond being sustainable? Isn’t the path we are on already good enough? What about net-zero design – isn’t that enough?

- How can we change the way we design to create a transition a regenerative construction industry? What influence do I have as a structural engineer? Isn’t this someone else’s job?

- How do we start to think systemically about the changes we need to make in industry to enable regenerative practice? How do we reinforce the positive changes we seek? How do re-imagine how supply chains?

- How do we begin to imagine a regenerative future? What are the ways of thinking we need to adopt? And what are the ways of thinking we need to leave behind.

Intrigued? Pre-order your copy here. Available in print or online.

Continue reading “5 questions on regenerative design”Role of the Regenerative Designer

All designers work to make things better. Regenerative design is a particular type of design because of its declared goals. This isn’t any kind of better. This is a specific kind of better, in which human and living systems can survive, thrive and co-evolve.

So while regenerative designers do lots of the things that regular designers do, (like developing a design brief, having ideas and testing these against the brief), there are two more things that make regenerative designers different. They must

- Hold a vision – hold and continually renew a vision for a regenerative future

- Create transition – Continuously be working to create a transition to that future.